The crossroads of Quatre-Bras was of strategic importance because the side which controlled it could move south-eastward along the Nivelles-Namur road towards the

French and Prussian armies at the Battle of Ligny. If Wellington’s Anglo-allied army could combine with the Prussians, the combined force would be larger than Napoleon’s. Napoleon’s strategy had been to cross the border into the Netherlands without alerting the Coalition and drive a wedge between their forces and subsequently to defeat the Prussians before turning on the Anglo-allied army. Although the coalition commanders did have an overview of French pre-war movements, Napoleon’s strategy was initially very successful.

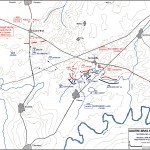

Caught on the hop by Napoleon Bonaparte’s brilliant surprise march that brought the French emperor within a few days march of Brussels and a potential political victory, the commander of the Anglo-Allied army, the Duke of Wellington, had to buy himself time to regroup. An advance French unit had been delayed at a vital crossroads at Quatre Bras by a small force of 8000 men from Saxe-Weimar and it was imperative that they were reinforced immediately. The crossroads was the link between the mainly British Anglo-Allies and the Prussians.

Maintaining an impassive front at a ball being held in his honour in Brussels, Wellington dispatched troops towards Quatre Bras as quickly as they became available. Fortunately for the Allies, the French commander Marshal Ney did not move quickly on the morning of the 16th and it wasn’t before 2pm that he sent forward General Reille with 20,000 men to clear the enemy away.

Within an hour they had seized two strong points on the Allied line, but struggled to clear Allied troops from woods that threatened the French left flank. Wellington arrived, as did the lead elements of British reinforcements, and the size of the clash moved from a skirmish to a full battle.

By late afternoon, the defenders had grown to some 26,000 men with 42 cannons and they were forced to withstand a ferocious attack by Ney. French cavalry reached the crossroads and, despite Wellington being forced to shelter in a square to avoid capture, the lines held. At 6.30pm, a further reinforced Wellington (36,000) moved forward and retook almost all of the ground lost to the French that day.

The Allies lost some 4800 men, while French casualties were 4000. It was a drawn clash tactically, but a major strategic blow for Bonaparte. The campaign could have ended on 16 June. If only Ney had been more active on the morning of the 16th and d’Erlons corps had made a contribution to either battle, the events of the next two days would have been very different.

I Corps would have made a difference at either battlefield. At Ligny, an envelopment of the Prussians with d’Erlons Corps would probably have meant the destruction of the greatest part of the Prussian Army. Instead a good portion of the Prussian Army engaged at Ligny escaped destruction.

At Quatre-Bras, a victory and a skillful pursuit would have sent the Allies running to Brussels instead of giving them the chance to reform themselves at Mont-St-Jean.