The Battle of Ligny (16 June 1815) was the last victory of the military career of Napoleon.

In this battle, French troops of the Armée du Nord under Napoleon’s command, defeated a Prussian army under Field Marshal Blücher, near Ligny in present-day Belgium. The bulk of the Prussian army survived, however, and went on to play a pivotal role two days later at the Battle of Waterloo.

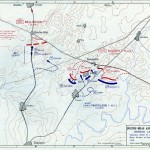

It was a bruising affair and began after he got the jump on his British and Prussian foes and had his army almost on them before they had time to react. Bonaparte’s plan for the 100 Days Campaign was to get in between the two armies and defeat each in detail before they could join together and outnumber him.

It was a toss of the coin to see who he would attack first, but the advanced Prussian

position at Ligny offered the perfect chance to knock Marshal Gebhard Blucher out of the war. The Prussians were in a strong position – sitting on ridges behind the Ligny brook and with several of the nearby villages heavily garrisoned – but Bonaparte had planned for a corps under General D’Érlon to hit the enemy on the flank and, together with a frontal assault, trap and destroy them.

The initial stages went well and after very heavy fighting the Prussians looked on the verge of collapse, but Marshal Michel Ney’s countermanding of D’Érlon’s orders delayed his arrival until it was too late to launch the killing flank attack.

Sending in the Imperial Guard finally broke the Prussians, who only managed to escape through the blind courage of the elderly Blucher who led a cavalry charge to save his army.

The Prussians still lost 25,000 men to Bonaparte’s 11,000, but were able to retreat in reasonable order along a parallel course to the British who had just beaten off Ney’s assault at Quatre Bras. Two days later would come the deciding battle at nearby Waterloo.

Although the French were victorious, their victory was not complete because a good portion of the Prussian army escaped destruction. Things would have been different if Ney, or even only d’Erlon’s Corps, would have arrived on the Prussian right flank. This would probably have meant the destruction of the Prussian I and II Corps, thus about half of Blücher’s army. With his forces so much reduced, Blücher would not have been able to march on Waterloo on 18 June and Napoleon would have won that battle and thus the campaign too.

Although Napoleon had missed the chance to win the campaign that day, his situation was satisfactory. The French had managed to keep the Allies from joining forces and Blücher was beaten, at least for now. Napoleon still had two fresh Corps (I and VI Corps) that he could use against Wellington so the chances for success were still very real that 16th day of June 1815.