the Neapolitan War. The phrase “les Cent Jours” was first used by the prefect of Paris, Gaspard, comte de Chabrol, in his speech welcoming the King. The Treaty of Paris 1815 was the peace treaty that ended the war of the Seventh Coalition against France.

The Seventh Coalition pitted the United Kingdom, Russia, Prussia, Sweden, Austria, the Netherlands and a number of German states against France. Traveling to Paris, picking up support as he went, Napoleon eventually overthrew the restored Louis XVIII. The Allies rapidly gathered their armies to meet him again. Napoleon raised 280,000 men, whom he distributed among several armies. To add to the 90,000 troops in the standing army, he recalled well over a quarter of a million veterans from past campaigns and issued a decree for the eventual draft of around 2.5 million new men into the French army. This faced an initial Coalition force of about 700,000—although Coalition campaign-plans provided for one million front-line troops, supported by around 200,000 garrison, logistics and other auxiliary personnel. The Coalition intended this force to have overwhelming numbers against the numerically inferior imperial French army—which in fact never came close to reaching Napoleon’s goal of more than 2.5 million under arms.

Napoleon took about 124,000 men of the Army of the North on a pre-emptive strike against the Allies in Belgium. He intended to attack the Coalition armies before they combined, in hope of driving the British into the sea and the Prussians out of the war. His march to the frontier achieved the surprise he had planned, catching the Anglo-Dutch Army in a dispersed arrangement. The Prussians had been more wary, concentrating 3/4 of their Army in and around Ligny. The Prussians forced the Armee du Nord to fight all the day of the 15th to reach Ligny in a delaying action by the Prussian 1st Corps. He forced Prussia to fight at Ligny on 16 June 1815, and the defeated Prussians retreated in some disorder. On the same day, the left wing of the Army of the North, under the command of Marshal Michel Ney, succeeded in stopping any of Wellington’s forces going to aid Blücher’s

Prussians by fighting a blocking action at Quatre Bras. Ney failed to clear the cross-roads and Wellington reinforced the position. But with the Prussian retreat, Wellington too had to retreat. He fell back to a previously reconnoitred position on an escarpment at Mont St Jean, a few miles south of the village of Waterloo.

Napoleon took the reserve of the Army of the North, and reunited his forces with those of Ney to pursue Wellington’s army, after he ordered Marshal Grouchy to take the right wing of the Army of the North and stop the Prussians re-grouping. In the first of a series of miscalculations, both Grouchy and Napoleon failed to realize that the Prussian forces were already reorganized and were assembling at the village of Wavre. In any event the French army did nothing to stop a rather leisurely retreat that took place throughout the night and into the early morning by the Prussians.[18] As the 4th, 1st, and 2nd Prussian Corps marched through the town towards the Battlefield of Waterloo the 3rd Prussian Corp took up blocking positions across the river, and although Grouchy engaged and defeated the Prussian rearguard under the command of Lt-Gen von Thielmann in the Battle of Wavre (18–19 June) it was 12 hours too late. In the end, 17,000 Prussians had kept 33,000 badly needed French reinforcements off the field.

Napoleon delayed the start of fighting at the Battle of Waterloo on the morning of 18 June for several hours while he waited for the ground to dry after the previous night’s rain. By

late afternoon, the French army had not succeeded in driving Wellington’s forces from the escarpment on which they stood. When the Prussians arrived and attacked the French right flank in ever-increasing numbers, Napoleon’s strategy of keeping the Coalition armies divided had failed and a combined Coalition general advance drove his army from the field in confusion.

Grouchy organized a successful and well-ordered retreat towards Paris, where Marshal Davout had 117,000 men ready to turn back the 116,000 men of Blücher and Wellington. Militarily, it appeared quite possible that the French could defeat Wellington and Blücher, but politics proved the source of the Emperor’s downfall. In any event Davout was defeated at Issy and negotiations for surrender had begun.

On arriving at Paris three days after Waterloo, Napoleon still clung to the hope of a concerted national resistance; but the temper of the chambers, and of the public generally, did not favour his view. The politicians forced Napoleon to abdicate again on 22 June 1815. Despite the Emperor’s abdication, irregular warfare continued along the eastern borders and on the outskirts of Paris until the signing of a cease-fire on 4 July. On 15 July, Napoleon surrendered himself to the British squadron at Rochefort.

Meanwhile in Italy, Joachim Murat, whom the Allies had allowed to remain King of Naples after Napoleon’s initial defeat, once again allied with his brother-in-law, triggering the Neapolitan War (March to May, 1815). Hoping to find support among Italian nationalists fearing the increasing influence of the Habsburgs in Italy, Murat issued the Rimini

Proclamation inciting them to war. But the proclamation failed and the Austrians soon crushed Murat at the Battle of Tolentino (2 May to 3 May 1815), forcing him to flee. The Bourbons returned to the throne of Naples on 20 May 1815. Murat tried to regain his throne, but after that failed, a firing squad executed him on 13 October 1815.

]]>

It is my wish that my ashes may repose on the banks of the Seine, in the midst of the French people, whom I have loved so well. – Testament of Napoleon, 2d Clause.

In 1840, Louis Philippe I obtained permission from the British to return Napoleon’s remains to France. The remains were transported aboard the frigate Belle-Poule, which

had been painted black for the occasion, and on 29 November she arrived in Cherbourg. The remains were transferred to the steamship Normandie, which transported them to Le

Havre, up the Seine to Rouen and on to Paris. On 15 December, a state funeral was held. The hearse proceeded from the Arc de Triomphe down the Champs-Élysées, across the Place de la Concorde to the Esplanade des Invalides and then to the cupola in St Jérôme’s Chapel, where it stayed until the tomb designed by Louis Visconti was completed. In 1861, Napoleon’s remains were entombed in a porphyry sarcophagus in the crypt under the dome at Les Invalides

]]>

death. The articles he had in his possession at Longwood he had wrapped up and ticketed with the names of the persons to whom he wished to leave them.

His will remembered many of those whom he had loved or who had served him. Even the Chinese laborers then employed about the place were remembered. “Do not let them be forgotten. Let them have a few score of napoleons.”

The will included a final word on certain questions on which he felt posterity ought distinctly to understand his position. He died, he said, in the apostolical Roman religion. He declared that he had always been pleased with Marie Louise, whom he besought to watch over his son. To this son, whose name recurs repeatedly in the will, he gave a motto – All for the French people. He died prematurely, he said, assassinated by the

English oligarchy. The unfortunate results of the invasion of France he attributed to the treason of Marmont, Augereau, Talleyrand, and Lafayette. He defended the death of the Duc d’Enghien. “Under similar circumstances I should act in the same way.” This will is sufficient evidence that he died as he had lived, courageously and proudly, and inspired by a profound conviction of the justice of his own cause. In 1822 the French courts declared the will void.

They buried him in a valley beside a spring he loved, and though no monument but a willow marked the spot, perhaps no other grave in history is so well known. Certainly the

magnificent mausoleum which marks his present resting place in Paris has never touched the imagination and the heart as did the humble willow-shaded mound in St. Helena.

]]>

But no amount of forced occupation could hide the desolation of his position. The island of St. Helena is a mass of jagged, gloomy rocks; the nearest land is six hundred miles away. Isolated and inaccessible as it is, the English placed Napoleon in its most sombre and

remote part – a place called Longwood, at the summit of a mountain, and to the windward. The houses of Longwood were damp and unhealthy. There was no shade. Water had to be carried some three miles.

The governor, Sir Hudson Lowe, was a tactless man, with a propensity for bullying those whom he ruled. He was haunted by the idea that Napoleon was trying to escape, and he adopted a policy which was more like that of a jailer than of an officer. In his first interview with the emperor he so antagonized him that Napoleon soon refused to see him. Napoleon’s antipathy was almost superstitious. “I never saw such a horrid countenance,” he told O’Meara. “He sat on a chair opposite to my sofa, and on the little table between us there was a cup of coffee. His physiognomy made such an unfavorable impression upon me that I thought his evil eye had poisoned the coffee, and I ordered Marchand to throw it out of the window. I could not have swallowed it for the world.”

Aggravated by Napoleon’s refusal to see him, Sir Hudson Lowe became more annoying and petty in his regulations. In all over the almost six years in exile, Lowe only saw napoleon six times. All free communication between Longwood and the inhabitants of the island was cut off. The newspapers sent Napoleon were mutilated; certain books were refused; his letters were opened. A bust of his son brought to the island by a sailor was withheld for weeks. There was incessant haggling over the expenses of his establishment. His friends were subjected to constant annoyance. All news of Marie Louise and of his son was kept from him.

It is scarcely to be wondered at that Napoleon was often peevish and obstinate under this treatment, or that frequently, when he allowed himself to discuss the governor’s policy with the members of his suite, his temper rose, as Montholon said, “to thirty-six degrees of fury.” His situation was made more miserable by his ill health. His promenades were so

guarded by sentinels and restricted to such limits that he finally refused to take exercise, and after that his disease made rapid marches.

His fretfulness, his unreasonable determination to house himself, his childish resentment at Sir Hudson Lowe’s conduct, have led to the idea that Napoleon spent his time at St. Helena in fuming and complaining. But if one will take into consideration the work that the fallen emperor did in his exile, he will have a quite different impression of this period of his life. He lived at St. Helena from October, 1815, to May, 1821. In this period of five and a half years he wrote or dictated enough matter to fill the four good-sized volumes which complete the bulky correspondence published by the order of Napoleon III., and he furnished the great collection of conversations embodied in the memoirs published by his companions.

Before the end of 1820 it was certain that he could not live long. In December of that year the death of his sister Eliza was announced to him. “You see, Eliza has just shown me the way. Death, which had forgotten my family, has begun to strike it. My turn cannot be far off.”

Nor was it. On May 5, 1821, he died.

]]>

Frenchmen: In commencing war for the national independence, I relied on the union of all efforts, of all wills, and the concurrence of all national authorities. I had reason to hope for success, and I braved all the declarations of the powers against me. Circumstances appear to me changed.

I offer myself a sacrifice to the hatred of the enemies of France. May they prove sincere in their declarations, and really have directed them only against my power. My political life is terminated, and I proclaim my son, under the title of Napoleon II., Emperor of the French.

The present ministers will provisionally form the council of the Government.

The interest which I take in my son induces me to invite the chambers to form, without delay, the regency by a law. Unite all for the public safety that you may continue an independent nation.” Napoleon

Napoleon himself at last recognised the truth. When Lucien pressed him to “dare”, he replied, “Alas, I have dared only too much already”. On 22 June 1815 he abdicated in favour of his son, Napoléon Francis Joseph Charles Bonaparte, well knowing that it was a formality, as his four-year-old son was in Austria. On 25 June he received from Fouché, the president of the newly appointed provisional government (and Napoleon’s former police chief), an intimation that he must leave Paris. He retired to Malmaison, the former home of Josephine, where she had died shortly after his first abdication.

On 29 June the near approach of the Prussians, who had orders to seize him, dead or alive, caused him to retire westwards toward Rochefort, whence he hoped to reach the United States. The presence of blockading Royal Navy warships with orders to prevent his escape forestalled this plan.

Finally, unable to remain in France or escape from it, he surrendered himself to Captain Maitland of HMS Bellerophon and was transported to England. The full restoration of Louis XVIII followed the emperor’s departure.

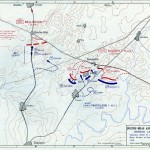

]]>slope of a ridge to protect them from artillery fire but with a wood behind which would delay any retreat if things went badly. Two strong points would dominate the battlefield, the farm houses of Hougoumont and La Haye Sainte, these would break up the force of the French attack throughout the day. Wellington had been promised help from the Prussian General Blucher and it would be the arrival of these reinforcements late in the battle which would finally turn the tide. On such a small and muddy battlefield there was little prospect of manoeuvres so the battle became a series of brutal frontal assaults by the French showing none of Napoleon’s typical skill.

The battle started on June 18, 1815 at around 11.30 a.m. One of the reasons for Napoleon’s defeat was that he delayed to initiate the battle as the ground was wet due to heavy showers the previous day. This gave enough time for the Prussian army to join the Wellington’s troops.

At 11.30 in the morning the French started their furious attack on Hugoument. Napoleon’s brother Jerome tried to take possession of the farm surrounding the war field. He involved his troop completely in the battle while Wellington stood obstinate. By 1.00 p.m. the Wellington troop started moving forward from the ridge and engaged the French army. Meanwhile, Napoleon received a message about the Prussian’s existence at St. Lambert and sent the Subervie’s and Domon’s cavalry to face the Prussians.

By four in the afternoon, the Prussians had started to arrive and the French had made little progress but attrition was starting to tell on the Allied forces. A last attack by the Imperial guard was routed and panic started to spread through the French forces. The battle was finally over. The allies lost 55,000 men and French 60,000, a horrendous cost prompting Wellington to say “Nothing save a battle lost is so terrible as a battle won”. Napoleon’s last great gamble had failed.

The Battle of Wavre was the final major military action of the Hundred Days campaign and the Napoleonic Wars. It was fought on 18-19 June 1815 between the Prussian rearguard under the command of General Johann von Thielmann and three corps of the French army under the command of Marshal Grouchy.

The march on Wavre, its influence on the result of the campaign, and the controversy to which Grouchy’s conduct on the day of Waterloo has given rise, are dealt at length in nearly every work on the campaign of 1815. Here it is only necessary to say that on the 17th Grouchy was unable to close with the Prussians, and on the 18th, though urged to march towards the sound of the guns of Waterloo, he chose instead to follow the Prussians along the route literally specified in his orders while the Prussian and British-Dutch armies united to crush Napoleon. On the 19th Grouchy won a smart victory over the Prussians at Wavre, but it was then too late. So far as resistance was possible after the great disaster, Grouchy made it. He gathered up the wrecks of Napoleon’s army and retired, swiftly and unbroken, to Paris, where, after interposing his reorganized forces between the enemy and the capital, he resigned his command into the hands of Marshal Davout.

The Battle of Wavre ended in a French victory with the Prussian rearguard in full retreat. To the Prussians the battle was a strategic victory, their rearguard had succeeded in holding off a superior French force long enough to allow Field Marshal Blücher to link up with Wellington’s Anglo-Dutch Army. Not only that, they had tied down some 33,000 French troops that could have otherwise taken part at Waterloo. Whilst Marshal Grouchy won at Wavre the victory was a hollow one as Napoleon’s main body of the L’Armée du Nord was defeated. If he had been more aggressive and gained his victory quickly Marshal Grouchy may have prevented Blücher from getting to Waterloo or even taken his own men there where they could have made all the difference.

]]>

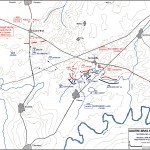

French and Prussian armies at the Battle of Ligny. If Wellington’s Anglo-allied army could combine with the Prussians, the combined force would be larger than Napoleon’s. Napoleon’s strategy had been to cross the border into the Netherlands without alerting the Coalition and drive a wedge between their forces and subsequently to defeat the Prussians before turning on the Anglo-allied army. Although the coalition commanders did have an overview of French pre-war movements, Napoleon’s strategy was initially very successful.

Caught on the hop by Napoleon Bonaparte’s brilliant surprise march that brought the French emperor within a few days march of Brussels and a potential political victory, the commander of the Anglo-Allied army, the Duke of Wellington, had to buy himself time to regroup. An advance French unit had been delayed at a vital crossroads at Quatre Bras by a small force of 8000 men from Saxe-Weimar and it was imperative that they were reinforced immediately. The crossroads was the link between the mainly British Anglo-Allies and the Prussians.

Maintaining an impassive front at a ball being held in his honour in Brussels, Wellington dispatched troops towards Quatre Bras as quickly as they became available. Fortunately for the Allies, the French commander Marshal Ney did not move quickly on the morning of the 16th and it wasn’t before 2pm that he sent forward General Reille with 20,000 men to clear the enemy away.

Within an hour they had seized two strong points on the Allied line, but struggled to clear Allied troops from woods that threatened the French left flank. Wellington arrived, as did the lead elements of British reinforcements, and the size of the clash moved from a skirmish to a full battle.

By late afternoon, the defenders had grown to some 26,000 men with 42 cannons and they were forced to withstand a ferocious attack by Ney. French cavalry reached the crossroads and, despite Wellington being forced to shelter in a square to avoid capture, the lines held. At 6.30pm, a further reinforced Wellington (36,000) moved forward and retook almost all of the ground lost to the French that day.

The Allies lost some 4800 men, while French casualties were 4000. It was a drawn clash tactically, but a major strategic blow for Bonaparte. The campaign could have ended on 16 June. If only Ney had been more active on the morning of the 16th and d’Erlons corps had made a contribution to either battle, the events of the next two days would have been very different.

I Corps would have made a difference at either battlefield. At Ligny, an envelopment of the Prussians with d’Erlons Corps would probably have meant the destruction of the greatest part of the Prussian Army. Instead a good portion of the Prussian Army engaged at Ligny escaped destruction.

At Quatre-Bras, a victory and a skillful pursuit would have sent the Allies running to Brussels instead of giving them the chance to reform themselves at Mont-St-Jean.

]]>In this battle, French troops of the Armée du Nord under Napoleon’s command, defeated a Prussian army under Field Marshal Blücher, near Ligny in present-day Belgium. The bulk of the Prussian army survived, however, and went on to play a pivotal role two days later at the Battle of Waterloo.

It was a bruising affair and began after he got the jump on his British and Prussian foes and had his army almost on them before they had time to react. Bonaparte’s plan for the 100 Days Campaign was to get in between the two armies and defeat each in detail before they could join together and outnumber him.

It was a toss of the coin to see who he would attack first, but the advanced Prussian

position at Ligny offered the perfect chance to knock Marshal Gebhard Blucher out of the war. The Prussians were in a strong position – sitting on ridges behind the Ligny brook and with several of the nearby villages heavily garrisoned – but Bonaparte had planned for a corps under General D’Érlon to hit the enemy on the flank and, together with a frontal assault, trap and destroy them.

The initial stages went well and after very heavy fighting the Prussians looked on the verge of collapse, but Marshal Michel Ney’s countermanding of D’Érlon’s orders delayed his arrival until it was too late to launch the killing flank attack.

Sending in the Imperial Guard finally broke the Prussians, who only managed to escape through the blind courage of the elderly Blucher who led a cavalry charge to save his army.

The Prussians still lost 25,000 men to Bonaparte’s 11,000, but were able to retreat in reasonable order along a parallel course to the British who had just beaten off Ney’s assault at Quatre Bras. Two days later would come the deciding battle at nearby Waterloo.

Although the French were victorious, their victory was not complete because a good portion of the Prussian army escaped destruction. Things would have been different if Ney, or even only d’Erlon’s Corps, would have arrived on the Prussian right flank. This would probably have meant the destruction of the Prussian I and II Corps, thus about half of Blücher’s army. With his forces so much reduced, Blücher would not have been able to march on Waterloo on 18 June and Napoleon would have won that battle and thus the campaign too.

Although Napoleon had missed the chance to win the campaign that day, his situation was satisfactory. The French had managed to keep the Allies from joining forces and Blücher was beaten, at least for now. Napoleon still had two fresh Corps (I and VI Corps) that he could use against Wellington so the chances for success were still very real that 16th day of June 1815.

]]>